Story highlights

Per capita, Dubai is one of the world's largest consumers of energy, largely for air conditioning

Sustainable cooling could come from adaptation of traditional Arabian wind towers

Small lightweight design developed by engineers could be applied to new structures

With its vast shopping malls, indoor skiing centers and artificial indoor beaches Dubai can lay claim to the dubious distinction of being one of the most air-conditioned cities in the world.

According to the World Bank, the emirate is now one of the largest consumers of energy per capita in the world – and an estimated two-thirds of that in the summer months is burned on driving air-conditioning.

Outside temperatures might reach a searing 50 degrees Celsius, (122 degrees Fahrenheit) but inside its public buildings the temperature can be so low that people wear jackets. At some cinemas customers can even rent blankets.

Energy consumption solely for air-conditioning is now one of the region’s looming headaches. According to Chatham House, neighboring Saudi Arabia could actually be consuming more oil than it exports in 15 years due largely to air conditioning.

Read more: Keeping the Qatar World Cup cool

The answer to this problem, however, could be closer to home than many previously thought.

Engineers are now looking at traditional Arab architecture as a way of providing zero-energy cooling for contemporary buildings, not just in the Arab peninsula but around the world.

The wind tower has been a fixture of Middle Eastern architecture for almost 1,000 years, says Ben Hughes, associate professor of building physics at Leeds University, and its solutions are as simple as they are effective.

“The higher up you go, the faster the airspeed is,” said Hughes.

“They used to build the towers as tall as possible, capture the air at high speed. As it hits the tower, there’s a wall that runs down the center of it that forces the wind down into the building.”

Read more: How not to approach a desert adventure

The build up of a positive pressure inside the building automatically creates a negative pressure on the outside, which means that stale and bad air inside the building is drawn away.

“It creates a siphon effect,” Hughes explained. “It pushes air into the building and sucks stale and used air out the other side of the wind tower.”

The most elegant examples of the wind tower still stand in Dubai’s historic quarter of Al Bastakiya – known locally as The Creek – where Persian traders created ornate structures built of stone or mud in the 1850s to cool and ventilate their urban mansions.

Often, the towers were wrapped in wet fabric to increase their cooling ability.

“They are absolutely fantastic,” Hughes said. “Anyone who’s been in one of these naturally ventilated space will tell you that it’s a far healthier environment than an air-conditioned space.”

Air-conditioning, he said, provides immediate thermal comfort whereas wind towers fulfill a different function, ridding buildings of the constant build up of CO2 and diminishing stuffiness.

Even so, his recently patented contemporary wind tower – a meter-high box that channels air down into buildings and cools it using gravity to feed a refrigerant liquid through a loop in the box – has achieved a temperature reduction of as much as 12 degrees in buildings.

Read more: Futuristic souk at heart of Dubai’s Expo

The beauty of his smaller compact design, he says, is that it saves on the cost of building a heavy and tall wind tower that puts a large structural and expensive burden on the construction.

“The idea of the small, lightweight design is that if you have more of them, you’ll get the same effect without having to pay the additional strengthening structural costs,” he said.

As energy costs rise, solutions based on the idea of the Arabic wind tower have become increasingly popular in European contemporary design over the past 10 to 15 years.

In the countries that gave birth to the concept such as Dubai – where air-conditioning, Hughes says, now accounts for 70% of electricity consumption in the summer – the wind tower is making a welcome return.

“The idea of taking this design back to the Middle East is that it’s part of their heritage,” Hughes said. “Qatar in particular has a strategic plan by 2030 to move to a knowledge-based economy and part of that plan is to provide healthy living environments that pays respect to their heritage so it fits really nicely with what they’re doing too.”

Read more: Building a hub for higher learning

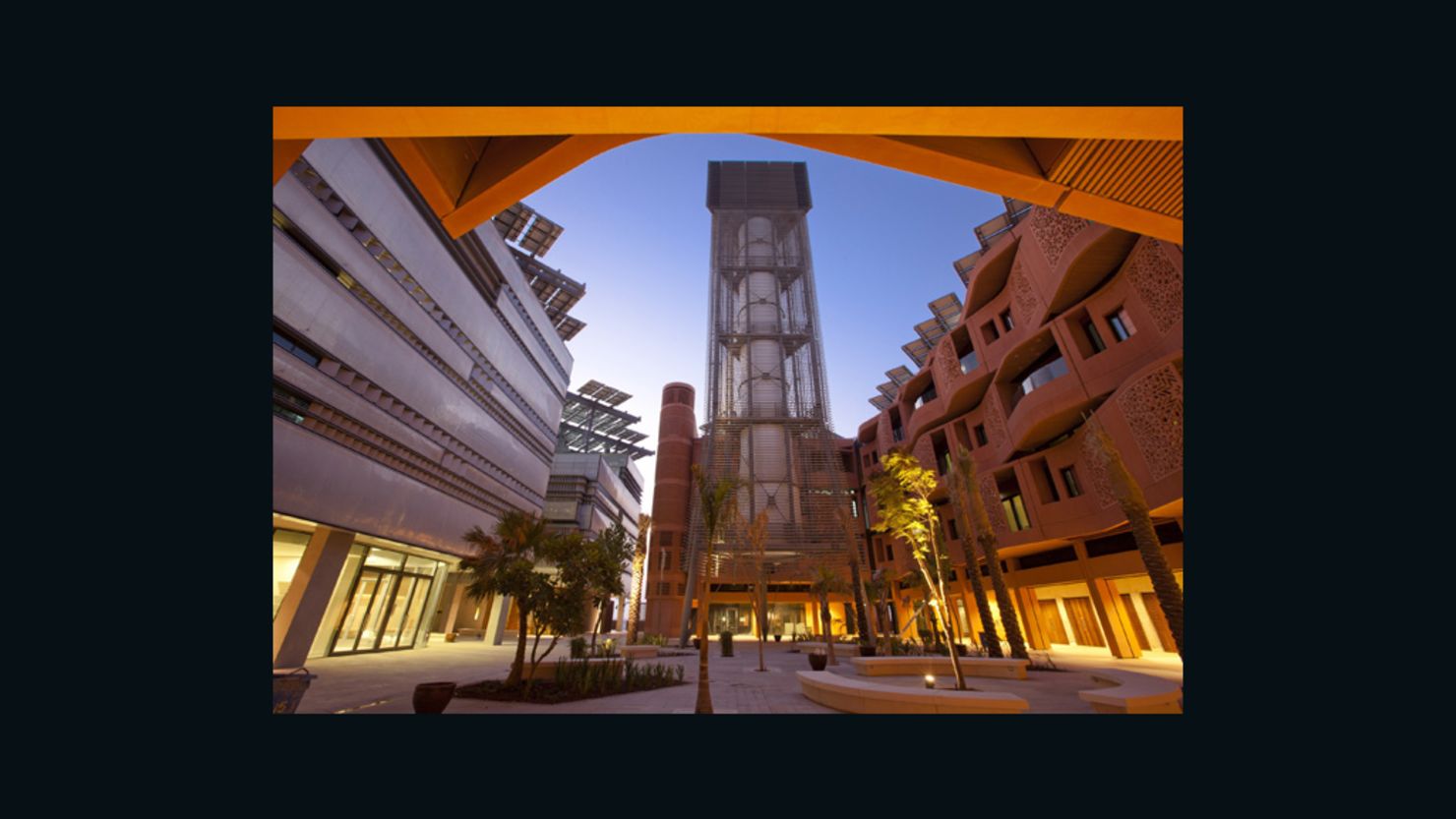

Masdar Institute of Science and Technology outside Abu Dhabi has one of the most spectacular examples of a modern wind tower, using the vernacular style of the traditional structures as part of a 45-meter tower that cools and ventilates the campus’ public space.

For Hughes, the answers to one of the Middle East’s most pressing problems – exponentially rising energy consumption to cool buildings in one of the world’s most inhospitable regions – was in its back garden all the time.

“It’s always been there but people are lazy,” he says. “If something allows people to control their space for minimal cost, they’ll take it.

“But as costs rise and decisions get harder about where you’re going to spend your money you need alternative solutions to provide comfort and that’s why we’ve taken a traditional technology and dragged it into the 21st century.”