Story highlights

There has been a flurry of ultra curvy building proposals of late

New research suggests our attraction to soft lines rooted in psyche

One design expert believes it's all related to sex

Are things looking a little wavy to you?

From London’s “Gherkin” to the “Marilyn Monroe” Towers in Ontario, when traveling through most of the world’s major cities, you’d be forgiven for thinking that town planners had tried to baby-proof new buildings by imposing a strict ban on right-angles.

Indeed, if a flurry of new landmark building proposals are anything to go by, things are about to get a whole lot curvier.

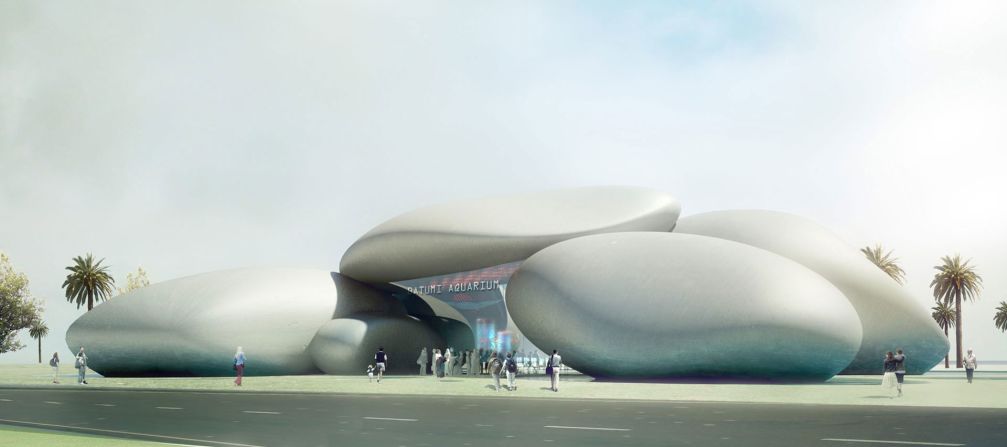

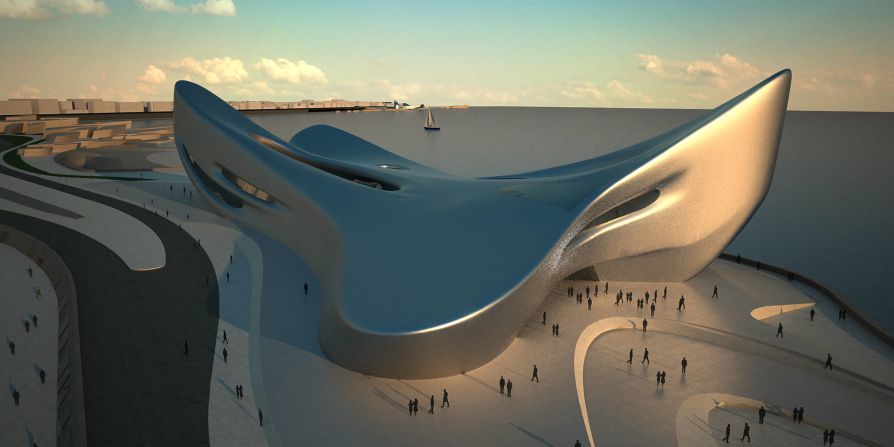

Last week, Zaha Hadid unveiled her design for the 2022 World Cup soccer stadium in Qatar. Inspired by the dhow, a traditional Qatari fishing boat, its sensual roof curves and bends, like a free-flowing sail in the wind.

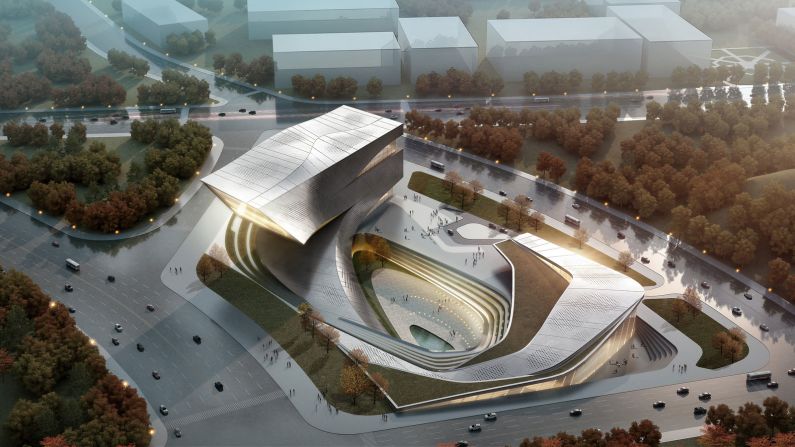

At the same time, the Cupertino city council gave Apple final approval for Apple Campus 2 – its massive new headquarters designed by starchitect Norman Foster. With an ultra-orbital shape and curving glass exterior, the building resembles a shimmering spaceship that has landed delicately in the fields of California.

And these are just two examples plucked from an ever-swelling list of proposed major structures with curling, sinuous and twisting features.

Nature vs nurture

It’s tempting to think that this wave of wavy buildings merely reflects the dominant fashion of the age. But a growing body of research suggests that a strong preference for curvy shapes may in fact be hard-wired into the human brain.

Read: How David Hockney became the world’s preeminent iPad artist

Psychologists have been toying with the idea that we respond to curves more positively than sharp lines for at least a century.

“Curves are in general felt to be more beautiful than straight lines,” announced psychologist Kate Gordon in 1909. “They are more graceful and pliable, and avoid the harshness of some straight lines.”

Now, more than a century later, a psychologist at the University of Toronto has put this conjecture to the test.

Oshin Vartanian and his colleagues slipped a group of people inside a brain-scanning machine and flashed hundreds of interior designs – some curvy, some angular – in front of them. They then had the choice of describing each room as either “beautiful” or “not beautiful.”

The study found that participants overwhelmingly preferred interior spaces with curving coffee tables, meandering sofas and winding floor patterns to rooms filled with angular furniture and rectilinear design.

But here’s the really juicy bit: Vartanian’s brain scans showed that curvy designs led to a burst of activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a region of the brain known to contribute to emotional experiences – whereas rooms filled with sharp corners and perpendicular lines did not.

In other words, it looks like our brain circuitry comes pre-installed with an emotional attachment to rounded forms.

But why?

Paul Silvia, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, believes that a positive response to curves may spring from our relationship with natural environments.

Between vast rolling hills and gently contoured flower petals, right-angles are a rarity in the great-outdoors. “Curved buildings can point to nature, whereas angular buildings contrast with it,” he says. “Instead of blending into the environment or evoking natural themes, they stand apart from it by using one of the few shapes you never see in nature—a perfect box.”

Read: 50 years since pop culture’s youth revolution

Silvia also points out that we’re all born attuned to human faces. As anyone who’s ever held a baby knows, their large round eyes frequently trigger uncontrollable feelings of warmth.

“Curved and rounded objects are so much more familiar that they seem more natural and ‘right,’” he says.

On the other hand, sharp objects can appear decidedly wrong. Research from Harvard Medical School found that the amygdala, the brain’s fear center, is significantly more active when people view angular objects, such as a sofa with sharp corners or a square watch, than when looking at curvier alternatives.

Rules of attraction

Hadid’s soccer stadium in Qatar has been compared to a vagina, a description she has distanced herself from. But Stephen Bayley, a British architecture critic and the former chief executive of London’s Design Museum, is convinced there is a sexual element in our response to curves.

“For reasons hidden in the foundations of the brain’s architecture, a curve, because it suggests warmth and well-being and harmony, touches a more profound part of the psyche than a parallelogram,” he says. “Maybe this is because a woman’s breasts are generally not right-angled.”

The instinct to appreciate curves may be hard-wired, but that doesn’t mean architects will follow the instinct indefinitely. Fads tend to fall out of favor, only to re-emerge years later.

Bayley remembers how, several years ago, Norman Foster constructed an “unapologetically square building” for his London headquarters. A few years later he built a “wantonly curvaceous” residential building right next door. There is a clear lesson. “At this historic moment curves get a high approval rating,” Bayley says. “But, as the rule of taste suggests, that will change again soon.”