Story highlights

In South Australia, a whole town lives underground to escape the heat

Think Seattle's nice? Try the city beneath it

Drainage systems sound dull but Tokyo's is an engineering marvel

Barmy about bunkers? Crazy about caves?

From Congress’s former nuclear shelter to the Viet Cong’s tunnels and a Parisian necropolis, here are some of the world’s best subterranean sights.

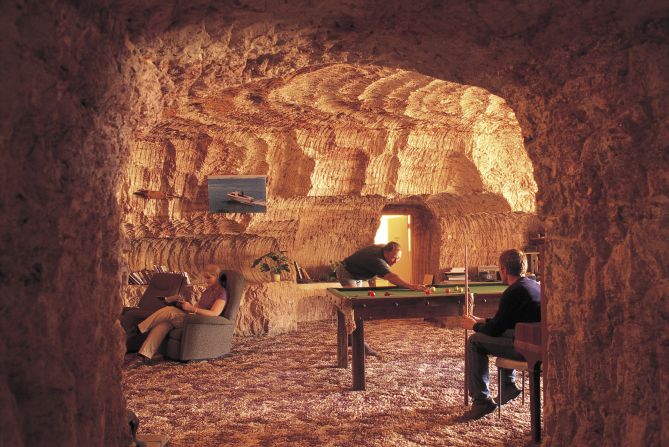

Coober Pedy, South Australia

Tourists wanting to channel their inner Hobbit should head to Coober Pedy.

Most of the South Australian town’s 3,000 residents live underground, where they frequent a subterranean church, restaurant, hotel and shops.

The town produces 70% of the world’s opal, and the blazing outback sun is the reason residents most prefer to live underground, as well as working there.

Coober Pedy comes from the Aboriginal term “kupa piti,” which means “white man’s hole in the ground.”

Find out more about Coober Pedy on the town’s website

More: More camels than koalas – 20 Australia discoveries

Wieliczka salt mine, Krakow, Poland

The Wieliczka salt mine, in southern Poland, was worked from the 13th century right up until 2007.

Now a two-mile-long section of Wieliczka – accounting for only 2% of the entire length of the mine’s passages – is open to the public.

Things to see include statues, a chapel and a cathedral carved out by miners, all under light cast by chandeliers made from rock salt.

Wieliczka salt mine, Dani?owicza 10, Wieliczka, Poland; +48 12 278 73 66; tours from $11.50

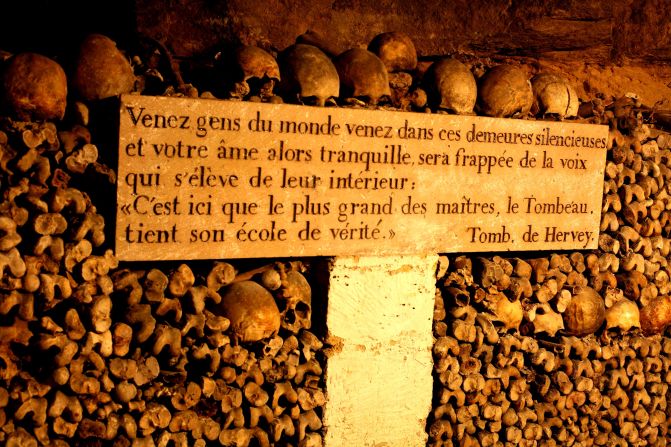

The Paris Catacombs, France

The catacombs of Paris are ideal for people who like their tourist attractions a little on the dark side.

The catacombs contain the remains of more than six million people whose bones were interred here between 1785 and 1860, when the city’s cemeteries became full.

A tour explores one mile of the 180-mile-long maze of tunnels, which lie at a depth of 20 meters.

The neatly stacked piles of bones within include the remains of many who lost their heads to the guillotine during the French Revolution.

Paris Catacombs; 1, Avenue du Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy, Paris, France; +33 1 43 22 47 63; tours from $5.50

Cappadocia, Turkey

The 200 so-called underground cities of Cappadocia – dense elaborate networks carved into the soft rock of the Turkish region, capable of sheltering thousands of people – may have been started as long ago as the 8th century BC.

Whoever built them failed to leave their initials on the walls but the Phrygians (an ancient Indo-European tribe) may have been responsible, with later expansion by the Persians.

It’s known early Christians hid in the man-made caves while they were still being persecuted for their religion.

Derinkuyu, extending to a depth of 60 meters, is the largest cave – it once housed 20,000 people, as well as their livestock.

Almost half of Derinkuyu is open to tourists. It’s connected to another subterranean settlement you can explore, Kaymaklli, via an eight-kilometer tunnel.

You can find out more about exploring the underground cities at Cappadociaturkey.net

More: How to drink raki: A crash course in Turkey’s signature drink

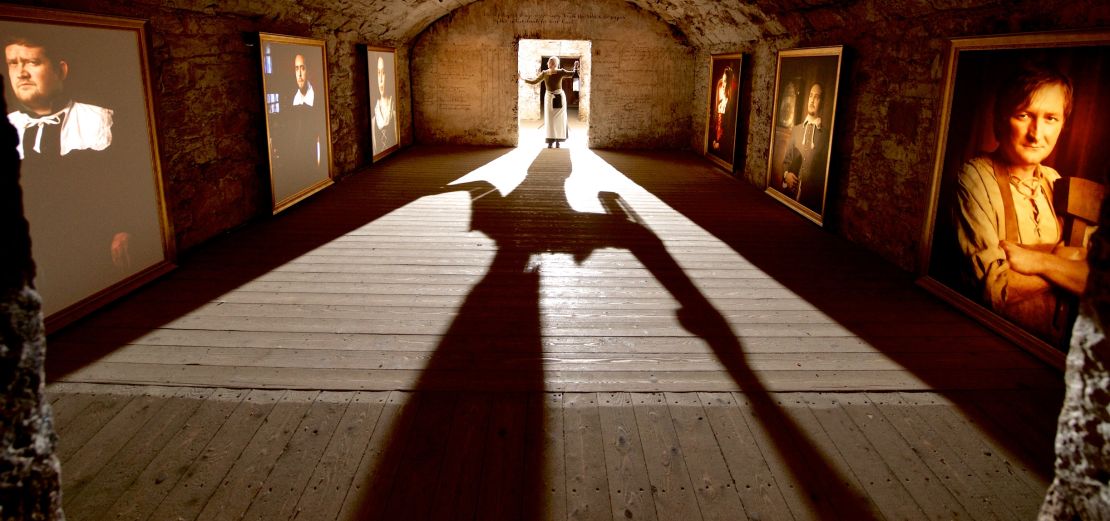

Mary King’s Close, Edinburgh, Scotland

Mary King’s Close didn’t used to be underground – it was Edinburgh’s busiest street until the plague struck in 1645.

The densely inhabited close was infested badly and a quarantine imposed on the 500 or so people who lived there in a bid to contain the disease.

Many of the inhabitants were simply left to die – hence the stories of hauntings.

The close was eventually opened up again and inhabited until 1753, when the residents were finally evicted to make way for new buildings built above the old street.

Mary King’s Close was sealed up for 250 years before being reopened for tours as a vivid snapshot of 18th-century life.

Mary King’s Close, 2 Warriston’s Close, The Royal Mile, Edinburgh, Scotland; +44 845 070 6244; tours from $11.60

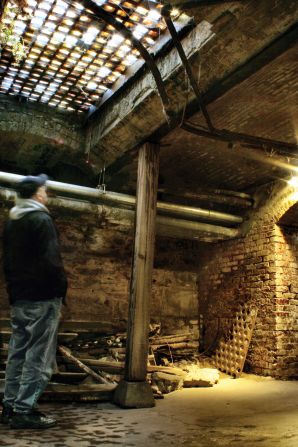

Seattle Underground, Washington, United States

When the Great Seattle Fire destroyed swathes of the city in 1889, municipal bosses decided simply to rebuild it one or two stories higher.

Built on mudflats, the original settlement had been prone to flooding.

Several oceans of concrete later, the new city rose between three and 10 meters above the old.

You can still visit the original Seattle, though, on a guided tour.

It’s fun to imagine the crowds once bustling along the shop-lined subterranean streets.

Seattle Underground, 608 First Avenue, Seattle, Washington, U.S.; +1 206 682 4646; tours from $9

More: Rooms with no view: Underground stays

G-Can flood surge tunnels, Tokyo, Japan

Anyone but claustrophobes should find this vast temple to underground engineering impressive.

Begun in 1992, the tunnels – 50 meters deep and six kilometers long and growing – contain pumps and tanks dedicated to keeping Tokyo dry during the rainy season.

The highlight is the enormous, temple-like main tank, which contains 78-horsepower pumps and is supported by 59 enormous pillars.

Tours of the complex take place three times a day, Tuesday to Friday – weather permitting, of course.

G-Can project, Ryukyukan Showa drainage pump station, Kasukabe, Saitama, Tokyo, Japan; +44 117 370 9751; tours from $13

More: Tokyo travel: 11 things to know before you go

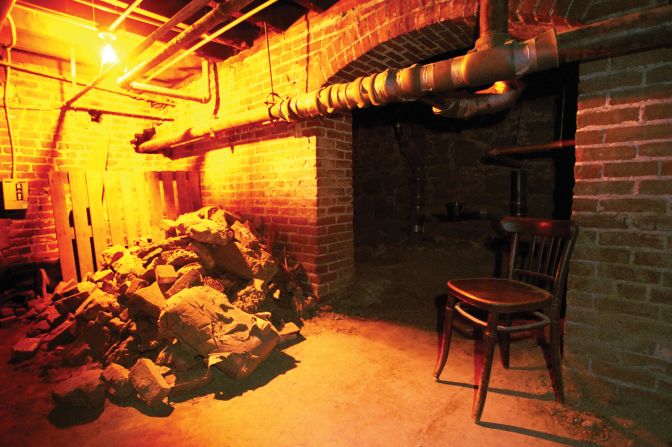

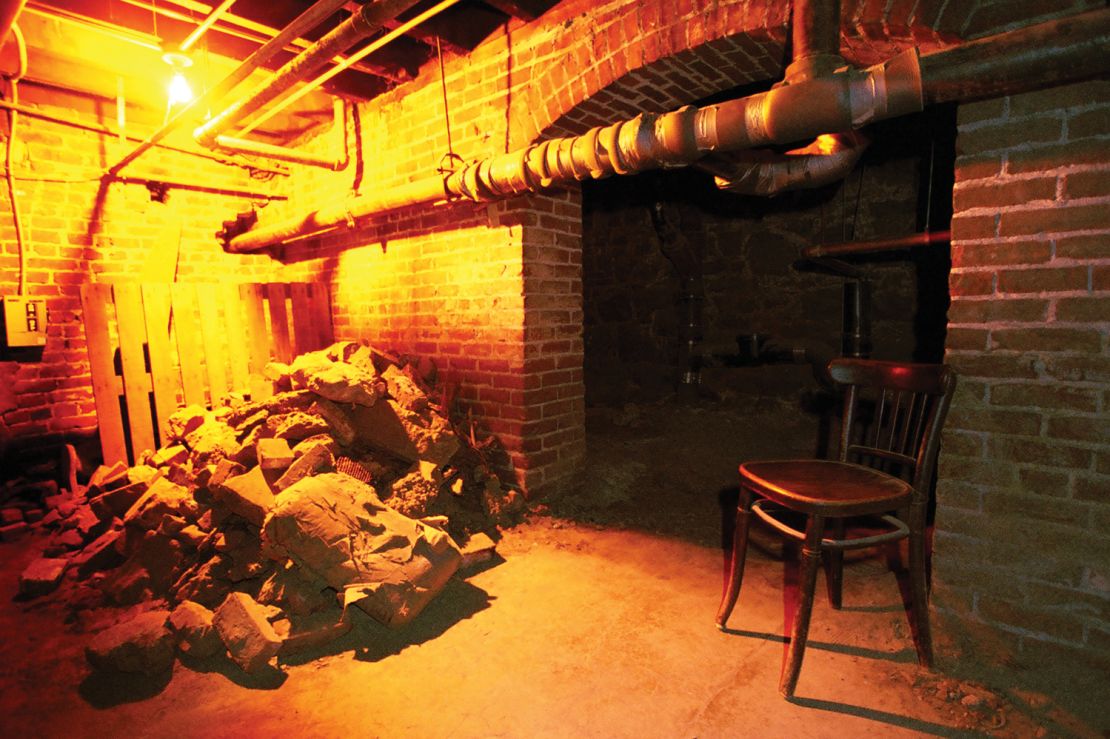

Shanghai Tunnels, Portland, Oregon, United States

The Shanghai Tunnels are a series of passages that connect the basements of many downtown Portland bars and hotels to the waterfront on the Willamette River.

Used prior to the 1800s to move goods from the ships that docked here, the tunnels got their name from the belief, probably false, that they were associated with “shanghaiing” – the practice of kidnapping men to serve as sailors.

Shanghai Tunnels, Portland, Oregon, U.S.; daily tours from $17

Greenbrier Bunker, West Virginia, United States

In the late 1950s, the U.S. government asked the owners of the 700-room Greenbrier Hotel, in West Virginia, for permission to build an emergency relocation center – a bunker – beneath the property, to house Congress in the event of a nuclear war.

Perhaps with some foresight (it’s now one of West Virginia’s most popular attractions), they agreed.

The bunker remained fully stocked for 30 years before being decommissioned in the early 1990s.

Daily tours of the facility inspect a 25-ton blast door, some of the 18 dormitories, a hospital and decontamination chambers.

Greenbrier Bunker, 300 West Main Street, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, U.S.; +1 855 453 4858; tours from $15

Cu Chi tunnels, Vietnam

The Cu Chi tunnels were used by the Viet Cong during large parts of the Vietnam War as living quarters, hospitals, supply routes and storage areas – even a tank was found in one of the tunnels.

This 120-kilometer-long complex, part of a much larger network throughout the country, now operates as a war memorial and visitors – or at least those who can squeeze through the tiny trapdoors – can explore several of the tunnels.

Impress Travel is one company that offers tours of the complex

Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, Canada

The tunnels built beneath downtown Moose Jaw in the early 1900s were intended to protect Chinese railway workers from persecution during the so-called Yellow Peril, the racist panic whipped up about thousands of Asian immigrants who’d arrived to find work.

Entire immigrant families lived in the tunnels while working above ground, but during Prohibition the tunnels were used for smuggling.

Al Capone was among the smugglers believed to have used the tunnels – daily tours are carried out by an Al Capone look-a-like.

Moose Jaw, 18 Main Street North, Saskatchewan, Canada; +1 306 693 5261; tours from C$8.50

City of Caves, Nottingham, UK

Bizarrely, the entrance to Nottingham’s cave network is located in the city’s Broadmarsh Shopping Center – but that’s a later development.

The caves were used as housing from the 11th century until 1845, when the St. Mary’s Enclosure Act banned the rental of cellars and caves as homes for the poor.

Archaeologists are still trying to work out how far some of the caves extend.

Visitors to the caves can see medieval wells and cesspits.

City of Caves, Broadmarsh Shopping Centre, Nottingham, UK; +1 115 988 1955; tours from $8.50