Story highlights

Sweden has a tradition of Eurovision success, having won the contest four times

It selects its entry each year through a televised national song contest called "Melodifestivalen"

The show is the highest rated program in Swedish history, more popular than Eurovision

Sweden's 2012 entry, "Euphoria" by Loreen, was the bookies' favorite to win

To the rest of the world, Sweden seems to represent all that is enviably European. Scandinavia’s largest country has a reputation for being stylish, progressive and glacially cool – in short, everything the Eurovision Song Contest is not.

So it may come as a surprise to some to learn that the Swedes take the annual song competition – occasionally viewed by some of their neighbors as a bit of a joke – very seriously indeed.

Unlike in many other western European countries, the privilege of representing Sweden at the annual contest is hotly contested, through a grueling series of televised heats which have grown to become more popular than Eurovision itself.

Melodifestivalen, a six-week, “American Idol”-style TV series in which established acts compete against unknowns for the honor of representing Sweden, has broken every local ratings record. Nearly half of the country’s 9.4 million people tuned in to this year’s final.

“Melodifestivalens is the Swedish equivalent to the Superbowl,” said Per Blankens who produced the TV show in 2006 and 2007.

“No other TV show gets the Swedes so rallied up. People put on dinner parties just so they can watch it together. They even get dressed up for the occasion.”

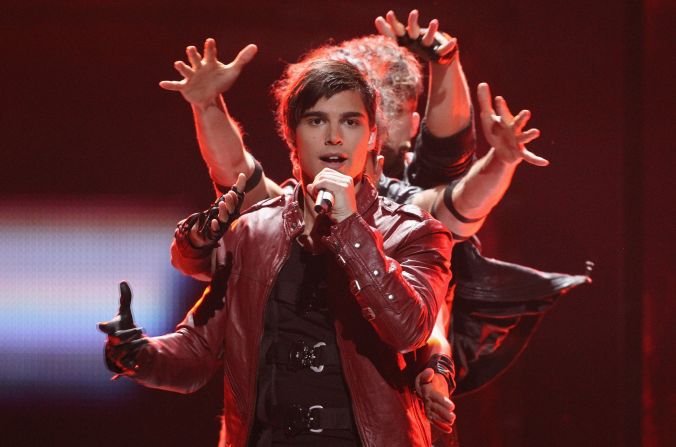

Forgettable song, memorable outfit: The crazy clothes of Eurovision

The show has proven an invigorating force for the Swedish music industry, reviving old pop careers, launching new ones and selling thousands of records and concert tickets in the process.

But why do the Swedes, often viewed as cool, collected tastemakers, get so worked up about a contest widely seen as having little musical credibility?

Proud tradition

“A lot of people don’t know this, but Swedes are obsessed with music,” said Blankens, who followed his stint on Melodifestivalen (Melody Festival) by producing the Swedish version of American Idol.

“Not only are all the most popular TV shows in Sweden music-related, but choral singing is the second most popular pastime after sports. It’s only natural for us to get worked up about a music competition.”

That love of music has translated to a long history of Eurovision success, with the most wins in the competition after Ireland (seven), France, Luxembourg and the UK (five each). The Netherlands has also won four times.

The love affair began when ABBA won the 1974 contest with their hit “Waterloo,” launching them on their way to becoming Eurovision’s greatest success story and one of the biggest-selling pop bands of all time.

The Swedish entry this year, “Euphoria” by Loreen, was the bookies’ favorite to follow in their footsteps and duly delivered success at the 57th Eurovision, in Baku, Azerbaijan.

The tradition of success has seen many Swedes grow up with “Melodifestivalen” and Eurovision as annual fixtures in their households.

“Watching Eurovision is a national tradition in Sweden,” said Maria Akesson, 28, a motion graphics student from Stockholm. “When I was a kid it was the only night, apart from New Year’s Eve, that my parents would allow me to stay up past midnight and let me eat as much crisps and candy as I liked.”

Even as an adult, Eurovision remains a big occasion. “I watch it with my friends and there’s always someone who will organize a house party where we’ll cook strange dishes from all the different countries and bet money on what song will win. People usually take the betting really seriously but we add silly categories like the worst outfit or the worst song.”

“Melodifestivalen“‘s timing – screening on Saturday nights for six weeks in the middle of the country’s famously gloomy winters – is seen as another reason for its enduring appeal.

“Sweden in the winter is very dark and can be quite depressing. When ‘Melodifestivalen’ starts airing in February we’re in the middle of this season, but every week leading up to the final is a week closer to spring,” said Sebastian Hjalmarsson Downey-Clark, a self-confessed Eurovision addict who works in London as a primary school teacher.

“It’s almost as if ‘Melodifestivalen’ is the vessel that carries Sweden from the dark of winter to the light of summer, and soundtracks that journey with some awfully catchy music too.”

Reviving the contest

“Melodifestivalen” is nearly as old as Eurovision itself, having run almost every year since 1959. But it wasn’t always such a polished affair.

“In the 1990s the competition was struggling. There weren’t enough good artists wanting to take part so it was decided that something radical needed to happen,” said Christer Bjorkman, a former hairdresser who won “Melodifestivalen” in 1992.

So in 2002, he oversaw the transformation of the contest from one-off contest between ten songs into a six-week pop marathon featuring 32. The ultimate winner is decided by a combination of public vote and a jury that consists of Swedish industry experts, and Eurovision judges from 11 other countries.

The new format, featuring knock-out semi-finals held in cities across Sweden, was a smash hit, and Bjorkman has been involved in the production of every contest since. Today he is known as “Mr Melodifestivalen.”

“Taking the show on the road was incredibly important to its success as it galvanized local support,” he said. “Equally as important was the fact that the audience now have weeks to familiarize themselves with all the songs. They form emotional attachments to the songs and, ultimately, also the winner – which is one of the reasons why so many Swedes still care about how we do in Eurovision.”

The resulting surge of interest in “Melodifestivalen” sees thousands of songs submitted to the contest each year, and has been a boon to the Swedish music industry. “It’s a goldmine for artists and songwriters that do well in the competition, as they go on to sell thousands of records and sell out tours across Scandinavia,” said Blankens.

Bjorkman agrees. “The competition is enormously important for the Swedish music industry because not only does it launch new careers and revives old ones, it sells a lot of albums too,” he said. “From winter until spring, our songs occupy the charts. The final was in March, but four of our songs are still in the top ten.”

‘Why not try?’

The Swedes are very aware that not every country shares their infatuation with Eurovision.

“Big countries who take themselves quite seriously – like Britain and France – don’t really want to compete against all these tiny nations on the European periphery in some silly music competition,” said Blankens. “They think it’s beneath them, so they keep sending bad songs that never win.”

But given the benefits to Sweden’s music industry from the country’s Eurovision obsession, perhaps the question shouldn’t be why does Sweden care, but why don’t others?

“Ultimately you get what you give,” said Bjorkman. “In countries like the UK they don’t give much – in fact they keep changing the format of the national try-outs each year. It’s no wonder the public has lost interest in … Eurovision.”

“Melodifestivalen“‘s success owes much to the Swedish tendency not to “do things by half measures,” he said. “When we decided to revive ‘Melodifestivalen,’ our aim was to create an amazing and engaging TV program that would benefit not only us as broadcasters, but the music industry and the viewers as well. I’m very proud to say that we have succeeded in doing just that.”